Zombies at the Theme Park

Consumers are waking from a long trance. There are profound implications for brands and creative professionals.

🎧 If you're a paid subscriber and you'd prefer to listen to this essay, just head over to the audio version of Zombies at the Theme Park 🎧

Introduction

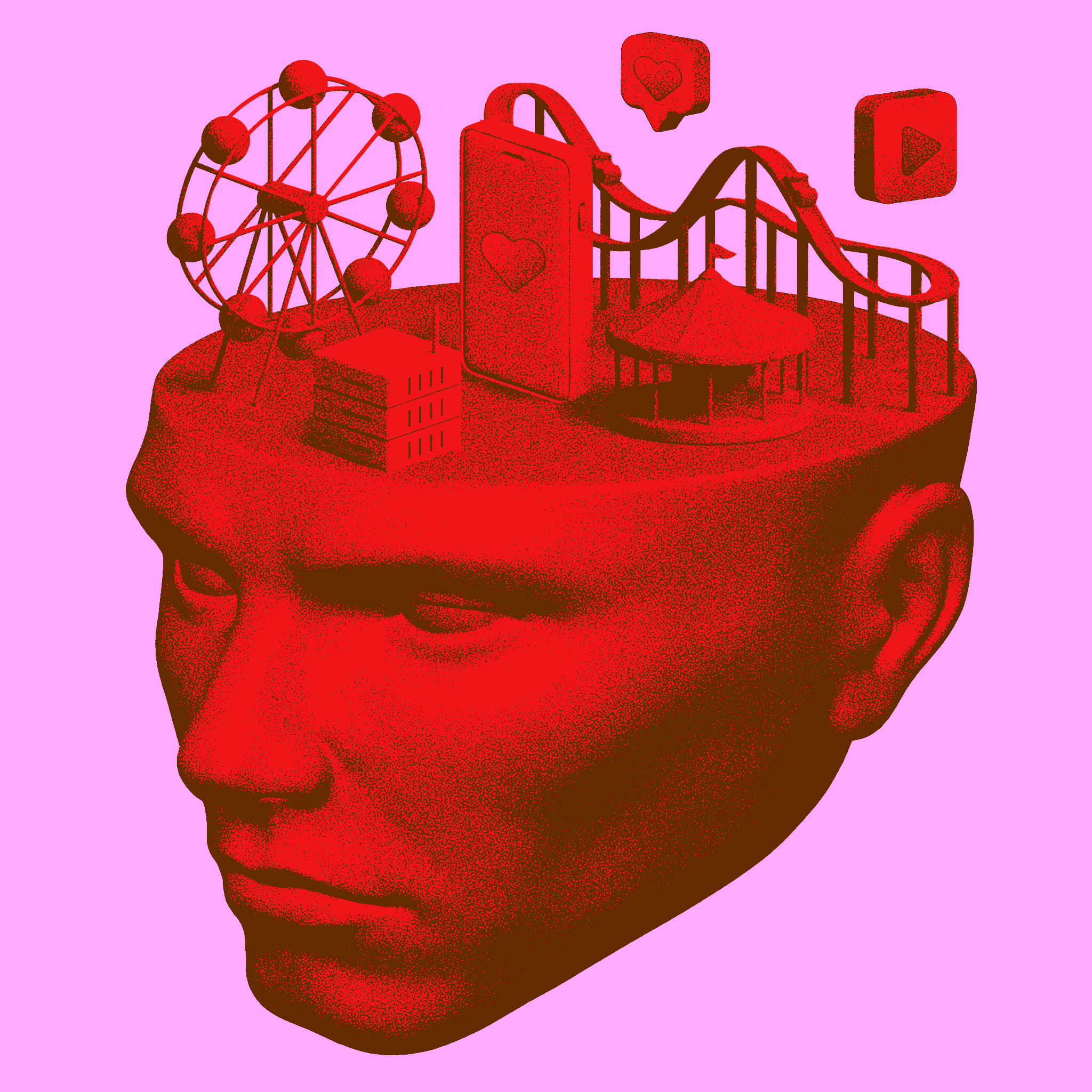

Here’s a thought experiment. Imagine a theme park so compelling, one that delivers such a powerful form of magic, that you’d be happy to stay there for the rest of your life.

This theme park knows you so well. It listens to everything you say, and watches every choice you make.

The park never forgets. It knows your history, every ride you’ve been on, every snack you’ve consumed. And over time it builds a model not just of what you’ve done, but of who you are; the deep, underlying beliefs, values, and preferences that drive your behaviour. It even uses sensors and AI to interpret your eye movements and pulse, so it knows when you’re excited, bored, or sad.

And via all that, the park can anticipate your every desire. It sometimes seems to know what you want even before you do. And then it delivers: endlessly, and instantly, without you ever having to ask. You never wait in line. You never feel frustrated. The next novelty will always be announced, just as the last falls away. Everything just flows.

It’s almost like a waking dream.

Now look up from the screen. This isn’t a thought experiment. You’re already in the park. You have been for years. And you know it.

*

This essay is about the our relationship with consumerism. And its core argument is as follows:

We inhabitants of technological modernity have built an all-encompassing machine for immediate preference satisfaction. Our societies model each of us not foremost as a citizen, or even a worker, but as a kind of sovereign individual: an axis of impulses that must be analysed, predicted, and served. An army of algorithms, delivery networks, streaming platforms, and AI assistants works ceaselessly to do just that.

The culture we inhabit sold this lifestyle to us as ultimate freedom. Have what you want, when you want it! And for a long time, most of us happily believed that. No one can deny the many ways in which our lives improved as the decades went by. But as we fell deeper into hyperconsumerism, it became harder to shake a strange new feeling. At first, it grew at the edges of our awareness. Perhaps the power to enact our preferences in this way was not real freedom, but something else? Something darker?

Lately, that feeling has grown acute. In 2026, we inhabitants of technological modernity are haunted by a deep unease. Its essence? We fear that the version of hyperconsumerism we’ve built has turned us into shadow humans; people who only give the appearance of being fully awake. We’re growing to see how the system around us perpetuates itself by keeping us in an altered state: distracted, addicted, stuck in the loop.

Our lives are materially comfortable beyond the wildest dreams of our great-grandparents. But the price we’ve paid is this unease. I’ve come to believe that it is best described in this way: our deep fear is that we have become zombies eternally lost in a theme park of endless preference satisfaction. Inside the walls of the park we live a surface existence, unconsciously consuming, clicking, and scrolling our way from one dopamine hit to the next, and never quite experiencing any of it.

But the way this feeling of unease is becoming acute, the way we are starting to talk about it, signals a shift. In 2026, the zombies — that means me, you, all of us — are waking up.

This awakening is, in my view, the most important socio-cultural trend in play in early 2026. And while various people are talking about fragments of it, I don’t yet see a coherent articulation of the broader picture.

In this piece, I want to attempt that articulation. I want to diagnose the zombified condition we've fallen into, and look at how the awakening is manifesting around us. And I want to draw out some key implications.

Our journey will take us through the mania for shortform video, to the new generation of activists who claim human attention is being fracked, to GLP-1s and their potential to radically transform our relationship not only with food, but with the entire system of hyperconsumerism as it exists now. And we'll see how immediate preference satisfaction has colonised ever-more of our lives, from our relationship with physical products, (thanks Jeff Bezos), through content (thanks TikTok algorithm) and now, via LLMs, to the final frontier: relationships.

Meanwhile, I'll argue that the zombie awakening has profound implications for all kinds of businesses and creative professionals. Implications for the way we design, the relationship brands build with their customers, and the kinds of products, services, and experiences that will have impact.

Two important qualifications before we begin.

First, I’m aware that when I say we’ve become lost in immediate preference satisfaction, that might sound as though I believe that life for everyone in 2026 is one endless round of consumption and material abundance. I am not under that misapprehension. Life is hard for many; wages are low, and plenty are struggling. But that’s one of the most insidious things about the theme park: the most potent distractions it serves are often low cost, or free. The park keeps the many distracted, while the few get rich. It’s enough to make you believe it was designed that way.

Second, if it’s not already clear: when I talk about zombies, I’m not trying to judge anyone. There’s a zombie in all of us; god knows mine takes control of me often enough. As we’ll see, this metaphor is really about the battle we all wage between two eternal sides of human nature.

To get started, then, I want to look at how our current condition — how our being lost in the theme park — manifests.

Then I’ll look at the mechanics of the mass waking event I say is happening now; that will mean taking a closer look at the way we humans experience the world, and ourselves. I’ll point to evidence that we zombies really are waking up. And finally, we’ll get to those implications.

So, let’s get into it.

Lost in the Theme Park

How does the theme park I’m talking about manifest itself in our lives in 2026? The answers, of course, are long and complex; we can only take the quickest glimpse here.

When it comes to moving towards an answer, there are so many possible avenues that we can take.

We could start, for example, with food. Our bodies evolved in an environment of scarcity; our brains are wired to seek salt, sugar, and fat. For most of human history, this impulse was constrained by the difficulty of satisfying it. Today, not so much. As we all know, so much contemporary food is processed food; preference-satisfying units optimised for compulsive consumption.

But the machine for preference satisfaction extends far beyond what we put in our mouths.

Consider the revolution in convenience services. Amazon, Deliveroo, Uber Eats, Instacart: these platforms have fundamentally altered our relationship with the acquisition of all kind of physical products.

We can think of this as immediate product satisfaction. The gap between desire and satisfaction has compressed to an extent that would have seemed impossible two decades ago. That new book? Next day delivery. Coffee from Starbucks? Thirty minute wait time. You never have to leave your sofa. You never have to plan ahead. Instead, in 2026 we operate the physical world as though via an all-powerful remote control.

The megasystem that Amazon has built to make all this possible now employs over 1.6 million people, making the company the world's fifth largest employer. Inside the vast temples to consumerism that it calls fulfilment centres, the scale of our wanting is made tangibly real:

But the most acute incarnation of the preference satisfaction machine? It’s not a part of the physical world at all. It is, of course, our online lives. Which for many of us now constitutes a great deal of our daily waking existence.

In retrospect, the internet was perhaps always best understood as a vast machine for the supercharging of our instinct towards instant preference satisfaction. Online, the gap between wanting and getting doesn’t have to merely shrink; it can disappear. And innovators have spent the last two decades leveraging that truth over and over, in ever more powerful ways.

We all know the mechanics by now. And they play out most acutely when it comes to a particular, and a vastly powerful, product. We’ve come to call it content.

The algorithm learns what you like. It serves you content that triggers engagement: a spike of outrage, a flicker of desire, a hit of validation. You didn't ask for this specific video, this particular post, this image. But the algo knew you would respond. You scroll. You tap. Hours dissolve. You emerge feeling hollowed out. They call you a user (as drug dealers do). But it feels more like the system is using you.