The Podcast Files — Episode 1

A transcript of the Full Moon Podcast

For those who prefer to read, here's a full transcript of episode 1 of the Full Moon podcast.

In this episode, Mark and David discuss the genesis of Full Moon, and their aspirations for the journey ahead. After that, they dive into a discussion of their launch essay, Where is Design Heading?

This transcript has been lightly edited for clarity. Occasional timestamps are included, to allow you to navigate to the relevant part of the video recording if you wish.

Happy reading!

Episode 1: Where is Design Heading?

David Mattin:

Hi there everyone, welcome to the very first Full Moon podcast. I am David Mattin and I'm of course joined by my Full Moon co-founder Mark Curtis. Mark, how are you?

Mark Curtis:

Hi everyone, very good, thank you.

David:

Now, this is an auspicious occasion, at least for us. We'll be doing this every month and the podcast is really a place for us to dive into the monthly essay. You all know that Full Moon is built around a deep dive monthly essay published of course on the night of the full moon. This is a place where we can really dive into that essay, interrogate it, investigate, challenge our own thinking.

And we've of course made the first essay free to everyone to read. It is the brilliant Where is Design heading by Mark. And we're going to dive into that essay in this first podcast. But before we do that, because this is the very first Full Moon podcast, it makes sense, I guess, for us to talk a little bit about why the hell we're here and who we are. So let's do something a little bit fun and introduce one another.

And I'm going to make you go first, Mark. You can introduce me and then I'll introduce you.

Mark:

Fair enough.

So, David, I first met you when you were a founder, I think, and leading writer and presenter at Trend Watching. And immediately there was a meeting of minds because quite a lot of what I did at Fjord within Accenture was to write and lead our annual Trends report. So David and I immediately had a lot of common ground. And I've seen him present and he's fantastic. He's a great writer.

Because he's an ex-journalist, he's adding a lot of discipline, which is much needed to the way in which I write, which I'm enjoying very much. And I think he's going to continue as part of our relationship. David also brings up other stuff which I don't do. So he writes for investors about economics and trends in that area in ways which I understand, but I couldn't possibly begin to write. And lastly,

I really love David's newsletter, which I've followed for some time now, New World Same Humans. And I think the title of that absolutely sums up a philosophy which we share, which is things are changing, but humans matter and the way humans behave, you know, is in many ways is both consistent over time and gloriously inconsistent as well.

So those are subjects we'll definitely be touching on more than frequently in full moon. So David, that's you, at least in my eyes. And now, uh-oh, you better describe me in your eyes.

David:

Thank you, Mark. And now it may now it looks like I made you go first because I knew you were going to say nice things about me. And I want to make it clear that that is not the case. That was not an enforced tribute to me. And that those can be that that can be the last time you say such nice things about me. Thank you very much. Just say say horrible things about me from now on to balance it back up. Now, who who are you to me? I became aware of you when I was at trend watching.

Trend Watching is a leading consumer trends firm. I wasn't a founder, I was sort of a partner there essentially ⁓ and became aware of Fjord, the digital design agency that you co-founded and looked up to you as a member in my eyes of just about, I think it's fair to say the generation above me, the people that pioneered sort of the first wave of digital and digital interaction who were there kind of at the beginning, realising, my God, this incredible thing has landed from outer space. What does it mean? How are we going to use it? How's it going to change the lives of people? And you and Fjord were sort of emblematic of that wave for me. And I loved the work Fjord was doing. It was so cool. It was so stylish. I loved the trends you did. And of course, we obsessively monitored all trends because that was our competition.

That was who Mark Curtis was to me. And then I remember Accenture acquired Fjord and that was interesting to me. So these huge and rather traditional players are waking up to this is now. The internet is life, digital is life. Okay, this is how this is gonna play out; they're going to, to a certain extent, absorb and co-opt these early pioneers. And that was fascinating to me. And then of course, I got to know you when you were at Accenture, we worked together on the Accenture Life Trends, which I think is just a brilliant annual trend report.

I was always deeply impressed with, you led the work on that and always deeply impressed with just the quality of thinking and writing in those Accenture trends. As you say, when we met there was a clear meeting of minds, we're interested in the same thing, had wonderful conversations, all of that, it was a joy to work, you know, then I ended up working on the Accenture Trends, it was a joy to do that. So that's who Mark Curtis is to me.

And that all taps into your first essay, you know, pretty nicely, which we'll dive into very soon. Before we do, why are we here? We've introduced one another, why are we here? What is Full Moon? How can we explain that to the listener?

Mark: (06:03)

So, Full Moon is a place where we want to explore ideas and we want to explore those ideas around technology, business and humans and the interaction between those because we are at an interesting, I mean, think we are at a, almost everybody concedes we are at a fascinating point globally at the moment in the way in which technology is developing.

It kind of went a bit flat and quiet in the late 20 teens and we wondered what the next breakthrough would be. And AI is definitely, initially we thought mistakenly it was a metaverse, but we got that wrong. And now it's AI and that clearly is really going to affect things. So I think now is a very good time to be thinking about that relationship between humans and technology and talking about it. And what we've done is to create a space where we can do that, but we can do it with other people as well. So we will be inviting guests on the podcast. We will be inviting guest writers. We definitely want to build on the commentary that people have on the things we've written and respond to those.

And over time, we have a vision of building up a community of people who are interested in those ideas and are interested in having a strong and frequent debate about what's going on in the world. Do you think that's a reasonable description of it?

David:

I think that's an excellent summary. And it's that kind of deep thinking at the intersection of technology, business, creativity, and what it means to be human that we're trying to tap into.

To me, a shorthand again for me for Full Moon is sort of Mark Curtis unfiltered, unhinged, totally liberated to say exactly what you think. And of course, I'm free to say exactly what I think. You know, it's that depth of thinking and insight and perception that I associate with the Life Trends report, but free from any constraints that might have been a part of life at a big corporation.

And we're free now to really go where we want, say what we want, think what we want for the fun of it, for the joy of it, but also to be useful and to help people do great work and flourish and navigate their careers and just make sense of all of this. We want to be joyous, but we want to be profoundly useful to people too. And publishing on the night of the full moon, I hope gives people a bit of an indication of where we're coming from. We're coming from a place that's slightly wild, slightly mad, certainly off center. But I think the times demand that that kind of ethic, right? There's nothing normal about what is playing out now. And in so many ways we want to figure out what is happening now, what it means for all of us, what it means for the way we work, how we live, the kind of work that's going to cut through the product services that are going to be meaningful. All of that.

I mean, we could talk on and on and on about why we wanted to do this. But I hope that gives people a good overview and then come on the journey with us and you're going to see what it is exactly we're trying to achieve here.

Mark: (09:30)

Can I add a couple of other things in? Apart from beyond the open permission it gives us to howl once a month at the moon, it's really important to us that young people engage with the world of ideas around work. And everyone's conscious of the debate which is happening right now about young people, jobs, the degree of difficulty of getting onto the ladder.

And so it's part of our vision that we can help in some, you know, small or larger way with exactly that. And to that end, one of the things we're doing is when people subscribe to Full Moon at the full subscription rate, then we give them the opportunity to give a free annual subscription to somebody age 28 or under. And that's super important to us to build that community and to help young people engage with ideas. Because I think that's very important.

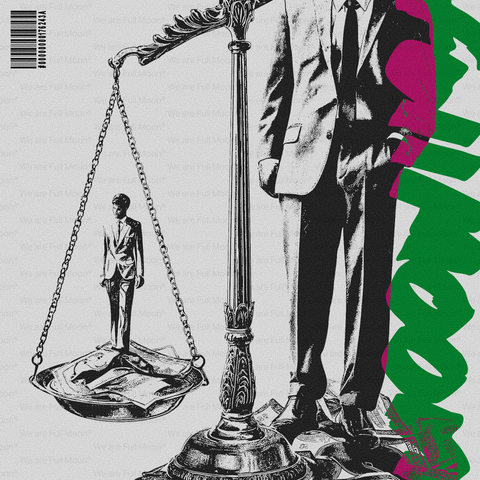

As part of that also, we will be looking to find young artists around the world to illustrate our monthly deep dive essay. And we're working with our wonderful designers, Paco and Julia, to do exactly that. They're actually illustrating the first two, but after that, we'll be getting into this swing of looking for creative talent who want to have the exposure that hopefully will come with being part of a Full Moon piece.

Anything else, David? I think one thing we've discussed a little bit is a lot of the voices that we listen to and enjoy listening to are either American or Brits writing in America and talking from there. there are some very well-known thinkers and podcasters and writers who are doing exactly that. And clearly America is just deeply, deeply important to the trajectory of all the things we've talked about. But there's also, I think, space for European voices here, for voices to say, this is what we're seeing and doing and thinking about. And I think that's not at the leading edge of what we do, but it's an important component of what you and I hope to achieve.

David:

Yeah, I absolutely love that.

I think, you know, Full Moon is unashamedly opinionated. It's the view from where we stand, you know, we're drawing on, I hope, you know, lots of experience and background to give a point of view on this collision of technologies, creativity, business, and so on. And part of that is, yeah, it's a European point of view. It's where we stand in Europe and the UK.

And in so many ways, you know — and we've talked about this privately too — you and I want to see a resurgence of our relevance and cultural heft and technological heft. I think that's absolutely fundamental to a meaningful future for us in Europe and in the UK. And anything we can do to, well, you know, it needs to be talked about, it needs to be supported. And I hope in some tiny way, bringing young people into our fold will also be helpful with that.

I mean, all the indications I get from the young people I talk to is that unsurprisingly, it's just bewildering and brutal out there for them now. If you're a young creative, a young consultant, a young knowledge worker, you're launching into an absolutely bewildering time where the future is so uncertain. mean, that's a sort cliched stock phrase, but it's just such a difficult time for someone in their 20s to start navigating and we want to help them make sense of that. So all of that in my mind is aligned and makes great sense. And I'm excited to see what we can do with a community of young creatives and knowledge workers and designers and where we can help them go and what we can learn from them too.

Now, with all that said, we are here, as we will always be, primarily to discuss the monthly essay published on the night of the full moon, usually to paid members. The first one is free. It's an absolutely brilliant essay. Where is Design Heading? If you haven't read it yet, go and check it out. Free to read, absolutely brilliant, mind-expanding piece of work. Let's dive into that, Mark. And I think a good segue into it is just for you to talk to us all about why that as the first essay, why did you want to write that piece now? Why did you want it to be your first piece of work for the Full Moon community?

Mark: (14:17)

So in the introduction we've just done, I hinted already at the idea that I think artificial intelligence and associated technologies are going to create an enormous spasm of change over the next, I mean, hey, your guess is as good as mine, one to 10, I would say 20 years, because I think it's going to take a long time to play out, even if there are some dramatic changes, which will happen fairly quickly, the actual consequences won't be clear for a while.

And I think because I was deeply involved with design at the beginning of the digital revolution, and people can argue about when that was, but I'm just going to say, I think it was sort of the mid nineties when people began to understand what was going to happen and the internet began to get into people's hands. Because it was clear then that design was going to be very important and was going to be changed by it. I think we're at another inflection point where we need to think about what we've done over the last 30 years and pull lessons out of that and understand how can we apply those to what we, what now needs to happen. And I think there are some very big questions over design.

As I make clear in the essay, when I talk about design, I'm talking about it in a very broad brush way. I'm not saying specifically this is about people who have a job title called designers. I believe many of us actually are engaged in design on a day-to-day basis. If we're designing how a CRM system works, or we're designing a brand, or we're thinking about how a product goes to market or we're actually looking at how do I structure things internally so that we can create products and services and experiences and deliver them out into the world from any one organization. All of that is design, in my view. So, yeah.

David:

Yeah, and this is a crucial aspect of your essay is is that any human made artifact is designed, you know, design is a part of the making of anything. Is that right? And that's why we all need to be, we're all to a certain extent designers, and we all need to be thinking about design, or is that taking it too far?

Mark:

No, I don't think that's taking it too far. I think people with designer in their title are those who are paid to think very, very hard about how to go about the process of design. But the reality is that a lot of people who don't have design in their title are by default doing design anyway. They're figuring out how something should work. And the ones who do that best think about the intent behind the design and the way in which the human interacts with it.

And specifically, that's why design really took off or digital design really took off in the early days was because we had to look at how people were interacting with things through screens, which largely speaking, we hadn't done before. know, TV was not an interactive medium up until, you know, the mid 90s. know, whether or not it is now is another question.

But we had to begin to think about the person on the other side of the screen and what they were doing. And that became a very specialist subject, which is where the rise of digital design came from. I would argue the same thing is true now with AI. We're starting with the technology. This always happens that you start with the tech and then people step back and take a deep breath and go, hang on a moment. What about the users here? How do we think about them?

And how do we now structure the technology around their needs rather than the needs of the technology?

David:

This is a crucial, that's a crucial point for me. I mean, there's, think there's a tendency for someone like me to, when I think designer, I to think, you know, graphic designer, someone literally designing images or posters or for me to think sort of furniture designer. But this is a form of, this, this is a way of thinking about design that encompasses, you know, perhaps you're making a website, you're even perhaps you're designing an internal culture or a kind of system inside your organization, all of those things are forms of design.

Mark:

Yeah, I mean, I was with a car company yesterday and it was a CX department and a large part of the conversation was about what happens not just online, but what happens in the dealership when somebody rocks up and says, I'm thinking about buying a new car, can you help me? And that's actually an incredibly important part of their experience.

I don't think most of the people in the room, any of the people in the room would actually tag themselves as designers, but they're definitely designing when they think about that systemic flow through where you might initially go look at a range of cars on the internet ⁓ and then actually you make the transition to moving to look at one specific website, possibly an app, and then into a dealership and then what happens there.

That journey needs to be designed.

David:

When we're talking about designing, you know, so a big, at the fundament of what you're saying in the essay is there were the early days of digital and this need to design our interaction with this new technology. And you can feel that coming around again with AI. We're in the early days of a transformative technology and we need to design our interactions with it.

Does that mean designing our interactions with essentially like AI-fuelled apps, you know, with things like chat GPT? Or does it go broader than that?

Mark:

Let me just go back a stage, David, because you triggered a thought I just, I'm burning to say, and that is, we can't let the design happen by default or by accident. And actually, I'm going to say it, people may not like it very much, but typically, if you leave technologists to do the design, unless they are extremely design oriented, they're thinking in a very different way about how the interaction should work. They're not always thinking about it from the human or user perspective. And that's what needs to be adjusted at that stage.

But back to the main plot. You asked about what design with AI will mean. There's three different levels to think about. The first is, AI as product. So that's what chat GPT and Gemini and Claude are. So that's where I just go and interact with something. The second is AI is a feature within a product. So undoubtedly that is happening and we're going to see more of it. So ⁓ I have this wristband from Whoop which tracks my health and my exercise. And there is a actually very good AI coach which is part of it, which I can go and find in the interface. It's not the entire product. It's a feature within the product. And then the third thing that I think is going to happen is AI both as product and feature. And that's going to happen. There's very little of this that I'm aware of at the moment. When people look at AI and they begin to build entire products using AI and featuring AI from the ground up.

So that's equivalent to Uber beginning to emerge after Steve Jobs really delivered on smartphone, the smartphone promise on a stage in California more than 10 years ago now, much more than 10 years ago. And so you get these three levels. Now at the moment, I think we need to think very hard about the design of AI as product. So I think there's a lot missing in the design of ChatGPT and Gemini, for example. Not the least, and I use both of those on an ongoing basis frequently, but not the least, I just can't find the stuff I've done. So the directory and categorization is missing something fundamental and they're going to need to fix that.

But beyond that, it seems to me unlikely that the form factor will continue as it is. We've dived straight in with a chatbot form factor. Nothing in history suggests the form factor will stay the same. It's likely to change. And then I think you also need to think about the design of AI as feature. So if you're a bank and you're going to embed AI in your app, which is likely to happen in the midterm future,

How are you going to coach people how to use it? How do they expect to respond? How do you manage customer expectations? All of those things. that answer your question about what I'm thinking about?

David:

I find that a very helpful sort of three level distinction, you know, AI as product AI as feature and then sort of AI native, I guess you'd call it.

And as you say, mean, you know, chat GPT has been wildly successful three years. think it's been around roughly 900 million users, crazy revenue generation already. And they haven't even switched on advertising yet, which is surely coming, but the designed interaction feels fairly thin to say the least. mean, you know, there's no good way of sorting the chats particularly. You can kind of put them in project folders now, but that's pretty thin gruel. Weirdly enough, you know, this app doesn't even use its power as a large language model to sort of auto group your conversations. You know, that feels to me an obvious thing to do.

Mark:

Yes, good point.

David: (24:56)

So chat GPT does not use its large language model to sort of say, you it looks like this conversation and that conversation and that conversation are all linked together. I'm going to sort of put them in a useful group for you. It just accretes them in a list.

There's a point in the essay where you say one day chat GPT will look as laughably old fashioned as the kind of Yahoo 1996 online portal does to us now. And that really resonated with me. You I feel that strongly when I'm using ChatGPT. I'm almost reminded of being sort of seven years old and using my old Commodore 64 and kind of booting it up. And you've got the, for any kind of nostalgia addicts out there like me, you may remember this, you got the beautiful blue glowing screen and the blinking cursor and you typed your commands and felt very powerful. ⁓ I almost feel like I've been rewinded to that place, back at that kind of very simple text interface level of design, and that we're at the very beginning of a design journey with AI that for digital took us through point and click and then interactivity online and all of that. And what does that look like ahead for our interactions with AI?

Sam Altman is partnering with perhaps the world's most famous designer, Johnny Ive, to try and answer that question. And we're all waiting for the object they are apparently designing that is going to be the next evolution of our interactions with these large language models. reputedly, it's some kind of pebble or something. It doesn't have a screen. You just talk to it. spoken interactions with digital, I think it's fair to say so far have not had a great track record.

So how's that going to play out? We were at the beginning of a very, very interesting journey. And that just came across so powerfully in your essay.

Mark:

There's always, I mean, there's always a risk with those that you're, you know, again, you need to think about the user context. So sitting on a train, the risk is you look like the mad person muttering to yourself. ⁓ You know, and, but I'm sure they're thinking about that. I'm interested not just in, in where a physical device might go. I'm also interested in just the interfaces on existing software, on existing hardware, ⁓ phones, laptops.

and how those will change. And it pays off every time to stand in the future and look back and say, really? Is this going to stay like this or can we imagine ourselves in the future and imagine some other way in which this might look, which might be more compelling? And things, is remarkable how quickly things get out of date and how savagely out of date they can look and feel and be. don't know, but my kids won't watch black and white movies.

just flat, flat out refuse to watch black and white movies. So my wife tries very hard to get them to watch, you know, post-war Italian cinema. And they're not, they're not very interested. I think they'd like the film. They just don't like the black and white bit.

David:

Yeah, I mean, my boys are absolutely bewildered by anything that was this sort of invented, you know, before about 2010, essentially, you know, old phones, cassette players, anything like that. They have no clue. And all of this comes across so powerful in your essay, the sense of us being at the beginning of something now comes across so powerfully. And part of the wonderful way you're able to do that is because you were at the beginning of something back then 30 years ago. And so you're in that position of being able to say, look, I've kind of seen this before. I've been at the beginning of something and watched it evolve. And essentially the core argumentative strategy of your essay is, let me take you on that journey, the journey we went on through digital design and of course now it's going to be different, but we can draw some underlying lessons out of that journey.

I want to dive into some of the big lessons you draw out, but before we do, and you know I love this, so this is mainly for me, I'm being selfish, give us just a sense of the energy and the vibe of that era. We're talking sort of mid-90s, late-90s, this new thing had come along, and to me it just feels like it must have been such an energising time. Is that right? Is that how you experienced it at the time?

Mark:

It was incredible. It was a very wonderful period to be working and thinking. ⁓ Several things came together. think one of them was finding talent. So Mike Beeston, who co-founded a company, the first digital company that I ran, Mike was amazing at going out and finding talent. And he found Anti-ROM, which was a collective that had largely been put together around a course, the very first course, I think in interaction design, I think that's what it was called, at the University of Westminster. I mean, these were really young men and women doing design no one had done before, trying to tackle issues no one had tackled before about how that would work.

And they created an artefact called Anti-ROM. They also called their collective anti-ROM. And I remember Mike and I looking at it, it was a CD-ROM. We just in a warehouse in Bermondsey and we sat and looked at this and we had a group of people and everyone went, I don't know what it is, but it's amazing. And I think that moment of in a way you're born along with the energy of something new and fascinating, even if you can't quite define it. Playing with that fuzziness of being uncertain was just fantastic.

And we had, you know, I went to a meeting with an innovation group at Allied Domec, who at that stage were one of the world's biggest drinks companies. And we explained what we were doing. And they literally commissioned us on the spot to do interactive kiosks between pubs and to create the world's first gay online community, which we call Planet Patrol. And we sold these projects in like two hours and we more or less invented the budget on the spot. And they said, yes, we were stunned, but then we had to go and deliver. And the delivery turned out to be really hard because nobody had the template for what sort of team do you need in order to deliver these things. And we had to literally make it up as we go along, which was extremely uncomfortable, but wildly exciting.

David:

Yeah, I just love it. And you know, I'm obsessed with anti-ROM. We've discussed this extensively. You know, I mean, I love what you say about the picture of them. You've got the essay, which is that they look like Radiohead, you know, they look like a band. They have that kind of vibe about them. And I've become quietly obsessed with kind of Googling them now and reading all about anti-ROM. And I desperately want an anti-ROM essay from you. ⁓ One that's just sort of dives into that era and bathes in the nostalgia.

Mark:

We should, I'm still in touch with several of them and we should let maybe one of them do it, because that would be super interesting. And they were every bit as cool as they look in the photograph.

David:

It would be so cool. You know, it makes me ask, where is the anti-ROM of now? You know, where are the young people now? You know, and I don't want to sound foguish and old, like I'm saying they're not out there. I'm sure they are out there. But where, who are they? Where are they? And what work are they doing?

Mark:

And here's the thing, so AI lends itself to them as a creative tool more than anything I've ever seen.

I have moral reservations about AI at a societal level, so I'm not a sort of unbridled evangelist for it, but there's no question that AI allows, permits, encourages a creative revolution in people simply being enabled to think up new ideas and deliver on them at significant speed. And I think we should be really, really excited about that.

A lot of the energy, a lot of the center of the narrative around AI has been, I think, very disappointingly about efficiency how can we make our businesses more efficient? It's a perfectly reasonable question. But I don't think there's been enough debate about growth. And I think that enabling growth is what AI is going to be best at doing. I certainly think it'd be very sad if it's just a more efficient way of doing the things that we do at the moment. And I don't think that's where it's gonna go.

David: (34:44)

And it feels like, again, this is a common path we always tread with technology. A transformative technology arrives and the first thing we try to do with it is just sort of get slightly better at the things we were doing in broadly the way we were doing them before. And it just takes, I think there's a huge amount of impatience associated with AI. People are sort of like, it hasn't changed everything yet, so it's all a fad, it's all a load of nonsense.

And it's like, it's going to take time for us to figure out what this technology really is, what we can really do with it. It's going to take time for it to diffuse through organizations because people still move at the speed of human. know AI moves very rapidly, but people on the whole do not move so rapidly. It takes time for them to learn and change and figure stuff out. And again, it feels like we're just at the beginning of all of that with AI.

Mark:

There's, there's, felt for a long time that there are three places where innovation come from. So, I should say three catalysts for innovation. So catalyst number one is technology. Here's a technology. That's cool. What can we do with it? And that's actually a lot of the phase that we're in with, with AI or have been for the last three to four years.

The second catalyst is business need. And that's typically where a lot of the AI action is happening now is how can we innovate around a business need to make ourselves more efficient, for example, or shorten our supply chain. And those are catalysts for innovation as well, those questions. The third, which is the almost mythical one, is starting with the human need. Mythical because in our heads we all have the narrative about the founder entrepreneur sitting on a beach somewhere in the world and saying to themselves, why was my journey here so difficult? Or why can't I rent that beautiful apartment over there? And out of that comes Uber and out of that comes Airbnb. And that's that catalyst is human need.

And I think where we go next with AI is — and you just said it, I loved what you said earlier — AI native. We head to this AI native place where people will be sitting on park benches or in cars or sitting up in bed one night and going, ⁓ hang on a moment. That's a problem. We can fix that. And that catalyst is usually the most powerful source of innovation.

David:

Yeah. And I think, I mean, one of the big lessons you draw out from the early days of digital is, you know, simplicity as a design principle. And obviously Steve Jobs is the sort of icon of beautiful simplicity, you know, and you talk about a design principle and you talk about the iPod and the click wheel, you know, just the iPod took, and if you're not as old as us, you won't remember this, but it took MP4 players, which were these sort of ugly black boxes with 7,000 different buttons on and turned it into this kind of sleek pebble with just one wheel and no instruction manual.

Just beautiful simplicity applied as a design principle. You talk about that in the essay. And I feel like we sort of, haven't nailed, we're nowhere near nailing. I mean, again, look at ChatGPT. We're nowhere near nailing what beautiful simplicity looks like even for kind of AI as a product. know, chat GPT is not delivering beautiful simplicity to me.

Mark: (38:28)

It was interesting because we, I mean, I do talk about this in the essay, but we, had an incredibly memorable conversation back in the mid 20s, 2000s, 2000, must've been 07, 08. And we could see Mike, who I referred to earlier in particular, could see, complexity coming because we were moving from a place where most people's digital interactions were on screens roughly the size I'm looking at through a keyboard and a mouse to a place where you would be swiping, scrolling, touching. Even your location would be a form of interaction. And you would be doing that on a variety of devices with very different affordances, screen sizes, types of screen, things they could do, including and then eventually your car as well, and your speaker in your house and God help us your fridge — I'm not sure that one's ever really been that meaningful.

As a result, what that means is you're dealing now with a user who's you're throwing complexity at them and that's not going to work. You've got to make it as simple as possible. But at the same time as making it simple, you have to make it elegant. And we actually discussed that word a lot and we discussed beauty and I know you just used beautiful simplicity instinctively which was interesting. We decided that clients would probably not fully buy into the word beauty and so we substituted the word elegant which has worked I think extremely well for us ⁓ instead of beauty. Beauty was almost too hard, too difficult a word for clients to get their heads around — I'm not in the beauty business — but I think most people would agree they probably should be in the elegant simplicity business.

David:

I can see why clients go for that more. It sounds a bit more useful and usable. I mean — and people need to dive into the essay because we can only scratch the surface of it here — you go on to talk about the design thinking wave, which to me, I so associate Fjord with design thinking, and you draw out some really interesting aspects of that, and you talk about design doing, design culture.

You know, just a huge, a huge kind of moment for digital design or wave of thinking around digital design that perhaps can help inform what is coming.

Mark: (41:06)

I had very mixed feelings about the popularity of the idea design thinking. I literally, as I say in the essay, when I saw it on the Harvard Business Review as a cover story in 2015, all of the alarm bells went off in my head that this would be the next management fad and it would survive for five years.

And then there will be articles saying design thinking doesn't work. And that is exactly what has happened. Now, I, despite those naysayers, I think actually what happened with design thinking as so much else we've talked about is that it became embedded in organizations.

And if it's gone away, it's gone away because it's just become something people do, which is to think harder and use various tools, you know, the cliche is, you know, Post-it notes and writing on walls, but to use various tools in order to think much, much harder about things from a user perspective and to think harder about who those users may be and begin to imagine oneself in their shoes. And I think all of that is what was embodied in embodied in design thinking, which has become, I think, in some companies, most companies probably has become second nature.

David: (42:34)

Yeah, that feels to me that that is what happened to design thinking, that it essentially became more or less the air we breathe, you know, and the idea that, and this goes back to the very top of the conversation, so it's a nice place to start to wrap it up, the idea that we are all in some sense designers or in some sense, or many of us are engaged in some form of design, and that any form of thinking about how another human being will receive and experience something you are making is a form of design and design thinking.

Mark:

So I want to pick up on, because you're sending me a signal, I can tell that we need to wrap this up and you're right. But I want to pick up on that word experience you just used, which I think you're absolutely right, is nobody used the word experience in business, except probably Disney.

Nobody used the word experience up until the mid 90s. And that's because it wasn't something people thought about very hard. mean, a few retailers probably thought about it, but generally it wasn't a thing. It was digital that made experience a thing. And Joseph Pine, and I think Pine and Nagel captured that in their legendary 1999 book, The Experience Economy. And now, I mean, like I said yesterday, I was with a CX team from a large, very well-known traditional European automobile manufacturer and experiences embedded in their job titles. That was unthinkable in 1994. And so probably we're going to see something similar happen now. We won't drop experience, which has moved to the heart of businesses, but something else will emerge with AI. Some other word, which actually then embodies a series of concepts and ideas and ways of doing things like experience, which is going to be very important to the way we conceive of business going forward.

David:

Before we do wrap up, cannot resist one more question. And this one is something of a challenge to you.

In the last few years of your work at Accenture, a lot of your thinking was around sustainability and around sustainability as the future of design or sustainability at the heart of design and the need, the imperative for that. Where does this AI revolution leave all of that? You know, I mean, we know that there's incredible AI infrastructure build out is going to take these data centers use huge amounts of energy. They also use a lot of water because of the cooling requirements. you feel that? mean, how you experience, here's this word again, experiencing, how you experiencing that personally and what do you think the big moment is? Are we going to forget about sustainability because of AI?

Mark:

Brief answer, I hope not, but I'm very worried.

I'm worried because I do passionately believe that climate change is the biggest challenge that the world faces at the moment. And I've read the evidence extremely carefully, and I think the evidence is all out there that that is the case. What I have discovered over the last three to four years is that

There's quite a lot of people out there who pay lip service to that, but are not actually particularly interested in engaging with it. that business need, particularly business needs around efficiency in a very tough economy and global economic environments over the last three to four years, mean that it's been very hard for businesses to focus on sustainability in the way that some of us, including me, would like and believe needs to happen. I think the second thing that has happened is there's been an unfortunate shift in politics. Unfortunate, if like me you believe climate change is real, I think there has been an unfortunate shift in politics, which is deprioritizing, in some cases aggressively, the sustainability agenda. And businesses are sensitive to that because they exist in a public realm.

And then I think the third thing that has happened is that AI has sucked all of the oxygen out of the room, and money, as we know, and it's all going into data centers, chips, cooling. We can see this in the US where consumer electricity bills are now beginning to rise quite rapidly. And consumers are beginning to put two and two together that this is down to the energy usage of large data centers being built somewhere near where they live.

As can tell, I probably I feel pretty passionately about this. However, my experience has been it's very hard to create change in that space. And to some extent, personally, I'm thinking about, okay, so what contribution can I make here if we can't get the attention that that subject deserves?

David: (48:03)

The intersection of sort of sustainability and what's happening now with technology is absolutely fascinating and it's one we'll come back to.

I mean, for people out there, I think few people understand the scale of the infrastructure build out that's happening. It is at a historic level comparable to the building of the railroads in the US, the spending now by the kind of five big technology companies is going to exceed the total spending on the Apollo moon program. We're talking about this level of infrastructure spending. And then of course, there's, you know, this, is the other part of my life is speaking essentially to investors and economists about all this. And it's a different kind of conversation over there, you know, that they are quite focused now on, this a bubble and is it all about to burst? And are we building, you know, multi hundred billion dollar data centers that we're never going to use because the demand won't be there? So all to be discussed.

Look, as you said, and as I said, we have to wrap this up. We could go on for another 50 minutes. We've only scratched the surface of what is such a brilliant and deep essay. If you haven't read it yet, go to Full Moon, check it out wearefullmoon.com. It's a brilliant read. Throw your comments and questions at us. You can comment on articles. You can comment on the page where this podcast is embedded, we will come back to you. We think we want to do periodical sort of question time style podcasts where we answer reader questions. You know, that will be a thing. So please do pepper us with your questions. And there's just so much more coming. I mean, you know that I want that anti-ROM essay or that anti-ROM oral history. I've got some pieces in mind I want to write about human freedom and the way that's manifested in the internet age, the kind of strange kinds of unfreedom we live with now, what that means for all of us, what that means for brands too, what they can do about it.

And you've got plans coming up, right? Not least, your second essay. Give people a tiny little teaser of that. That's a nice way to close this out. Tease the second part of your essay, which will of course be published on the night of the full moon in January.

Mark: (50:22)

So it's very much an extension of what we've in the first one, we're looking back going, what can we learn from what, what has evolved with design over the last 30 years, the design of products, services and experiences. The next one is about what comes next and how do we begin to frame that? How do we think about it? What jobs need to be done and who's going to be doing those jobs and trying to get to the heart of how we think about designing AI products, services and experiences. And the big clue is the job to be done is actually all about differentiation.

David:

And it has a title that I love. Are we allowed to say it?

Who gets to design the future when everyone can? I mean, a brilliant title. I cannot wait to read that essay. Part two, you know, the follow on of the essay we gave you this month. Look, it is high time to wrap this up. Thank you so much for listening. We will be back in your inbox soon. We'll be back with that essay that you just heard about on the night of the full moon in January. In the meantime, thank you for being a lunatic. We appreciate you.

And Mark, be well. I will see you again soon.

Mark:

Thank you, David, and thank you for listening. Bye, everyone. See you soon.

Comments